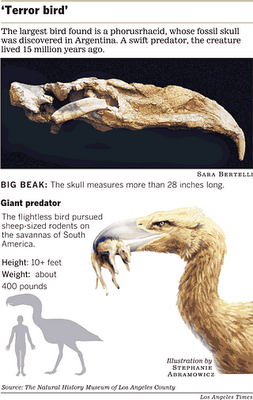

The LA Times carries the LA County Natural History Museum's announcement of the discovery of the largest fossil bird every found. There was no species name listed in the story, but the fossil skull, discovered in Patagonia, is related to an extinct group of birds known as phorusrhacids - "terror birds." He has been dated to the Oligocene, 15 million years ago.

I'd like to see one scaled against a moa. This new fellow looks quite a bit more robust than the herbivore moas.

5 comments:

And we think eagles are scary! These were a re-evolving of the Deinonychus niche I think...

I'll be interested to see what Darren Naish has to say about this!

Stay tuned...

(though give me a few days, things are pretty busy right now).

Oh, sure, the imprints are a bit nasty-tempered... But the passagers, once manned, are lovely little birds...

[Gulp!]

First things first, this wasn't the largest bird ever. Not even hardly.

190 kilograms makes the largest of the phorusrhacids the biggest predatory birds, hands down (OK, unless you accept Gregory S Paul's neoflightless phylogeny that actually nests the dromaeosaurids within aves). 190 kilograms does not make them even close to as big as a 400 kilogram moa (largest dinornis species), or hold a cnadle to the real heavyweights like dromornis stirtoni and aepyornis maximus (both around 500 kilos). Incidentally, 500 kilos may be a fundamental biomechanical limit on the maximum mass of ground birds, but then again, similar things were said about pterosaurs with eight meter wingspans!

I'm also disapointed by the art from the story. Phorusrhacids had really big eyes; their face would somewhat have resembled a contemporary bird of prey's. In fact, their eyes were somehat larger than would be expected from allometric dropoff in eye size in tetrapods. It's probably reasonable to say, then, that they had exceptionally keen eyesight (sort of like a huge, two legged sighthound).

And yes, they were quite stocky for a bird. The neural spines of the shoulder vertabrae are unusually tall for a birds. This suggests hypertrophy of the neck muscles, the better to shake things to death with I suppose.

This should not be taken to mean that they were slow, however. Unlike gastornids (the ones you always see in kids books flogging the dead eohippus), phorusrhacids had runner's legs. Some biomechanical computer models suggest that the smaller genera were as fast as cheetahs (although I have reservations about biomechanical models of long gone animals). One thing the picture does get correct is that their bills had a well developed hook. Between that and the ostritch-proportioned legs, there can be little doubt that these tough customers were scaring the bejeesus out of the various denizens of Tertiary South America (and quaternary Florida!). In fact, since most of the local mammalian predators were a rather sorry lot of slow-moving marsupials, the phorusrhacids were likely the top predators on the pampas.

There is one close-ish relative of the phorusrhacids alive today. Unless there has been some revolution in higher-level avian cladistics I've been completely ignorant of, the seriema is considered a fairly close relative of these magnificent predators. The seriema is sort of the South American equivalent of Africa's Secretary Bird. That's probably not a bad way to think of the phorusrhacids really; big, beefy and flightless secretary birds.

Regards,

R. Arthur Wilderson

Post a Comment