Every decade or so, technology requires us to lurch forward into modernity.

After almost 14 years, on the Blogger platform, Steve Bodio’s Querencia has been moved to a new WordPress website that combines blogging and a home for Steve’s writing life.

It’s

taken some time to drag 4200 posts and their 12600 comments to the new

platform, and it will take a little while for Steve to become

comfortable banging out more fascinating posts and replying to your

comments, so please be patient.

The Blogger site will remain up

but inactive, so your old links will still work. And you can use the

search function in the navigation bar to find the new version of the old

posts here.

Karen Myers, Behind the Ranges Press

Stephen Bodio's Querencia

"Stuff is eaten by dogs, broken by family and friends, sanded down by the wind, frozen by the mountains, lost by the prairie, burnt off by the sun, washed away by the rain. So you are left with dogs, family, friends, sun, rain, wind, prairie and mountains. What more do you want?" Federico Calboli

Monday, February 11, 2019

Tuesday, January 01, 2019

More Burkina Faso- and what one man can do...

Tom wrote this to an even better- known hunter:

Dear +++

I guess I don’t see a downside to “saying something.” Fear of looking ineffectual? Isn’t that exactly what we are being by not at least trying?

Slowly, by barking from the end of my chain, I have caught the attention of the former US ambassador to Burkina Faso (I will copy you on our e-mails) and Congressional staffers on the Hill and the US embassy in Ouagadougou. Sound pathetic? Perhaps, but I see progress.

OK, tune up the harps, what did Theodore Roosevelt hope to accomplish by raising the issue of saving North American big-game through the Boone & Crockett Club in 1887, or your country’s own John Harkin in the early 20th century? For that matter, what good did “Walden” or the writings of John Muir or “A Sand County Almanac” or Ding Darling’s cartoons do for shaping modern conservation? On the other hand, think of the immeasurable havoc “Guns of Autumn” continues to wreak upon us.

I think that before people act, they need to have an idea about what they are acting for. And I believe that hunter’s like you can help foster that idea.

Speaking entirely for myself, I feel obligated to raise this matter, even if nothing concrete comes of it. I owe habitat and wildlife and native peoples and, yes, the spirit of the hunt; and it’s time to try to repay.

We are certainly quick enough to rail against anti-hunters and PETA and “emotion-based” wildlife management and about all the “chassis,” to turn to O’Casey, in the world we once hunted so freely and all the other usual suspects when we think, often rightly, that they threaten hunting, even if that only amounts to “Oh, I didn’t know. Too bad...what’s for dessert.”

If you want a specific to-do list, and I certainly should have one to offer, start by informing at least the following of this, to make sure they are aware, or should that be “woke,” when it comes to Burkina Faso?:

Safari Club International

Dallas Safari Club

Boone and Crockett Club

Wild Sheep Foundation

Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation

Your Congressional delegation–or for you your Parliamentary one

Public figures (if you want to write the Prince of Wales, you must address the envelope by hand, include your initials in the lower left corner, and use “Dear Sir” for the salutation, to stand a ghost of a chance of its reaching his own desk and not halting at some equerry’s)

Fellow hunters, especially the rich ones, and in particular those looking for a”cause”

Newspapers

Broadcast News

Talk Shows

More

For myself, I have done that, and am even contemplating contacting, God forbid, the World Wildlife Fund, African Wildlife Foundation, Clinton Foundation. If I could get Sarah McLachlan to write a song about Burkina Faso, I’d ask her, too.

I can understand your thinking I’m chasing my tail, or that I’m purely delusional. I won’t argue with you about either score. Maybe when it comes to caring about the situation in Burkina Faso, you had to be there. I have been there, as have you, and calling it “beautiful” country is not enough for me. But I can only speak for myself about speaking for Burkina Faso.

If you want a completely grandiose, probably megalomaniacal, statement about what we may ultimately stand to lose when Burkina Faso burns is the entire system of hunting-based conservation in Africa that we have so fervently championed now for generations. And that for some reason, in this case, we seen disinclined to voice our support for, if by nothing else than decrying its destruction.

THE BATTLE CONTINUES...

He then got this from a former ambassador, and also got Doug Peacock, through me:

Tom,

Which narrative do you want me to send to the Embassy? This email or the concern expressed in a document you send to various places?

World Wildlife Fund, African Wildlife Foundation, Clinton Foundation, and multiple others are attempting to address many of these issues. Of course most need public support. They do in fact have programs to strengthen countries' ability to deal with environment and wildlife, as well as programs to educate the populace and do such things as micro-finance that helps women, especially, to contribute to their family. It has long been proven that focusing on girls' education will make a big difference in population, economy, good governance and health. And good governance includes environment and wildlife. We were making extremely good progress in Malawi on strengthening the country's policies and processes related to the environment and wildlife management. Funding was cut last year however.

I urge you to continue looking at what you and others with the same passion can do to make a difference short term and long term.

Jeanine

Dear +++

I guess I don’t see a downside to “saying something.” Fear of looking ineffectual? Isn’t that exactly what we are being by not at least trying?

Slowly, by barking from the end of my chain, I have caught the attention of the former US ambassador to Burkina Faso (I will copy you on our e-mails) and Congressional staffers on the Hill and the US embassy in Ouagadougou. Sound pathetic? Perhaps, but I see progress.

OK, tune up the harps, what did Theodore Roosevelt hope to accomplish by raising the issue of saving North American big-game through the Boone & Crockett Club in 1887, or your country’s own John Harkin in the early 20th century? For that matter, what good did “Walden” or the writings of John Muir or “A Sand County Almanac” or Ding Darling’s cartoons do for shaping modern conservation? On the other hand, think of the immeasurable havoc “Guns of Autumn” continues to wreak upon us.

I think that before people act, they need to have an idea about what they are acting for. And I believe that hunter’s like you can help foster that idea.

Speaking entirely for myself, I feel obligated to raise this matter, even if nothing concrete comes of it. I owe habitat and wildlife and native peoples and, yes, the spirit of the hunt; and it’s time to try to repay.

We are certainly quick enough to rail against anti-hunters and PETA and “emotion-based” wildlife management and about all the “chassis,” to turn to O’Casey, in the world we once hunted so freely and all the other usual suspects when we think, often rightly, that they threaten hunting, even if that only amounts to “Oh, I didn’t know. Too bad...what’s for dessert.”

If you want a specific to-do list, and I certainly should have one to offer, start by informing at least the following of this, to make sure they are aware, or should that be “woke,” when it comes to Burkina Faso?:

Safari Club International

Dallas Safari Club

Boone and Crockett Club

Wild Sheep Foundation

Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation

Your Congressional delegation–or for you your Parliamentary one

Public figures (if you want to write the Prince of Wales, you must address the envelope by hand, include your initials in the lower left corner, and use “Dear Sir” for the salutation, to stand a ghost of a chance of its reaching his own desk and not halting at some equerry’s)

Fellow hunters, especially the rich ones, and in particular those looking for a”cause”

Newspapers

Broadcast News

Talk Shows

More

For myself, I have done that, and am even contemplating contacting, God forbid, the World Wildlife Fund, African Wildlife Foundation, Clinton Foundation. If I could get Sarah McLachlan to write a song about Burkina Faso, I’d ask her, too.

I can understand your thinking I’m chasing my tail, or that I’m purely delusional. I won’t argue with you about either score. Maybe when it comes to caring about the situation in Burkina Faso, you had to be there. I have been there, as have you, and calling it “beautiful” country is not enough for me. But I can only speak for myself about speaking for Burkina Faso.

If you want a completely grandiose, probably megalomaniacal, statement about what we may ultimately stand to lose when Burkina Faso burns is the entire system of hunting-based conservation in Africa that we have so fervently championed now for generations. And that for some reason, in this case, we seen disinclined to voice our support for, if by nothing else than decrying its destruction.

THE BATTLE CONTINUES...

He then got this from a former ambassador, and also got Doug Peacock, through me:

Tom,

Which narrative do you want me to send to the Embassy? This email or the concern expressed in a document you send to various places?

World Wildlife Fund, African Wildlife Foundation, Clinton Foundation, and multiple others are attempting to address many of these issues. Of course most need public support. They do in fact have programs to strengthen countries' ability to deal with environment and wildlife, as well as programs to educate the populace and do such things as micro-finance that helps women, especially, to contribute to their family. It has long been proven that focusing on girls' education will make a big difference in population, economy, good governance and health. And good governance includes environment and wildlife. We were making extremely good progress in Malawi on strengthening the country's policies and processes related to the environment and wildlife management. Funding was cut last year however.

I urge you to continue looking at what you and others with the same passion can do to make a difference short term and long term.

Jeanine

Thursday, December 27, 2018

Burkina Faso

TOM McIntyre writes:

I am trying to bring the ongoing critical wildlife situation in Burkina Faso to the attention of people (literally anyone) outside that country. As you may know, Burkina Faso, Benin, and Niger provide habitat for the final viable herds of savanna big game in West Central Africa, including the last few hundred endangered West Central African lions. Now terrorism threatens the system that has supported the conservation of these animals and habitat. If allowed to go on unchecked, the herds, if not all the animals, in Burkina Faso, then Benin and Niger, will be gone in a disastrously short time. I would invite you to click on my timeline at Facebook (Thomas McIntyre) and read my several postings over the last few days on this unfolding tragedy. If there is a way of contacting you directly, I hope that I may. I wish you the best, and I am, very truly your, Tom McIntyre.

Background: For all of my nearly sixty-seven years, I have been fascinated by Africa, its environment, people, and wildlife. Over forty years ago I was able to make my first safari to Kenya, and have returned to the continent more than a dozen times. This has led to a career as a writer on outdoor topics and numerous books, including my latest, Augusts in Africa.

Last January, I was able to travel to and hunt in the nation of Burkina Faso; and it was extraordinary to see so much large wild fauna in West Central Africa–everything from elephants and lions through buffalo, Western roam, kob, hippo, crocodile, francolin, guinea fowl, all wild and free ranging. It was a small piece of Africa, but the concept of giving the wildlife value through safari camps to give the local people a stake in wildlife and wild-land conservation was clearly working. Then last week, in a series of e-mails from a contact of mine [Arjun Reddy], there was this (I will leave my friend’s words in their raw, unfiltered state so you can better judge the level of his outrage, frustration, and profound sorrow). Regrettably, in the current climate, I don’t think we can count on our government to take any action, at least not without its being prompted So it may be, indeed, up to us:

I am very sorry to inform you that the jihadists have burned down our camp in Burkina Faso last week as well as several other hunting camps. We had already cancelled the coming season! The eastern part of the country was always quiet but has suddenly become a hot bed of terrorist cells of al Qaeda SOBs.

Fortunately no one was in camp! The caretaker had gone for lunch…

They have burnt many camps now. Government is useless…if they [al Qaeda] set up camp in that area and make it a no-go area it will be the end of the wildlife. The elephants are already killed off, all the big ones, now they will finish the rest. Its very sad Tom. I want to set up a FB page to bring the world’s attention to this issue!!!

It’s a very sad situation as their plan is to create a base in that forest area and get rid of all the wildlife and government authorities. No doubt the game will all be gone if nothing is done about it soon...

Is there anything we can do to bring it to the attention of SCI [Safari Club International] and DSC [Dallas Safari Club–and I would add the conservation community in general: This is clearly a matter of wildlife, human rights, and terrorism] so they can lobby our government to put some pressure on the government of Burkina or raise attention to this situation!? Everything can be rebuilt but the game will be gone forever if this goes on for a few years! As it is they have wiped out the elephant bulls and now working on the cows and anything with even the smallest ivory!

Rather unwelcome words to share this time of year, even more so for me to hear–I knew this place, these people, these animals.

This letter represents a portion of what I am trying to do to raise awareness of this potentially tragic, for all of the three mentioned above, situation.

If there is anything you can do to bring attention to what could be the end of some of the finest savanna wildlife left in West Central Africa, I can only hope, with respect, that you will.

Thanking you for taking the time to read this letter, I am

Sunday, December 23, 2018

Two Autumn Poems

Every year I print these two poems. One was composed in the Connecticut River Valley in the 1950s. The other is from Provence ca 1925...

October Dawn

October is marigold, and yet

A glass half full of wine left out

To the dark heaven all night, by dawn

Has dreamed a premonition

Of ice across its eye as if

The ice-age had begun its heave.

The lawn overtrodden and strewn

From the night before., and the whistling green

Shrubbery are doomed. Ice

Has got it spearhead into place.

First a skin, delicately here

Restraining a ripple from the air;

Some plate and river on pond and brook;

Then tons of chain and massive lock

To hold rivers. Then, sound by sight

Will Mammoth and Sabre-tooth celebrate

Reunion while a fist of cold

Squeezes the fire at the core of the world,

Squeezes the fire at the core of the heart,

And now it is about to start.

By Ted Hughes, Collected Poems

Autumn

I love to seem when leaves depart,

The clear anatomy arrive,

Winter, the paragon of art,

That kills all forms of life, and feeling

Save what is pure and will survive.

Already now the changing chains

Of geese are harnessed at the moon:

Stripped are the great sun-clouding planes:

And the dark pines, their own revealing.

Let in the needles of the moon.

Strained by the gale the olives whiten

Like heavy wrestlers bent with toil

And, with the vines, their branches lighten

To brim our vats where summer lingers

In the red froth and sun-gold oil.

Soon on our hearth's reviving pyre

Their rotted stems will crumple up:

And like a ruby, panting fire,

The grape will redden on your fingers

Through the lit crystal of the cup.

By Roy Campbell, Selected Poems

October Dawn

October is marigold, and yet

A glass half full of wine left out

To the dark heaven all night, by dawn

Has dreamed a premonition

Of ice across its eye as if

The ice-age had begun its heave.

The lawn overtrodden and strewn

From the night before., and the whistling green

Shrubbery are doomed. Ice

Has got it spearhead into place.

First a skin, delicately here

Restraining a ripple from the air;

Some plate and river on pond and brook;

Then tons of chain and massive lock

To hold rivers. Then, sound by sight

Will Mammoth and Sabre-tooth celebrate

Reunion while a fist of cold

Squeezes the fire at the core of the world,

Squeezes the fire at the core of the heart,

And now it is about to start.

By Ted Hughes, Collected Poems

Autumn

I love to seem when leaves depart,

The clear anatomy arrive,

Winter, the paragon of art,

That kills all forms of life, and feeling

Save what is pure and will survive.

Already now the changing chains

Of geese are harnessed at the moon:

Stripped are the great sun-clouding planes:

And the dark pines, their own revealing.

Let in the needles of the moon.

Strained by the gale the olives whiten

Like heavy wrestlers bent with toil

And, with the vines, their branches lighten

To brim our vats where summer lingers

In the red froth and sun-gold oil.

Soon on our hearth's reviving pyre

Their rotted stems will crumple up:

And like a ruby, panting fire,

The grape will redden on your fingers

Through the lit crystal of the cup.

By Roy Campbell, Selected Poems

Saturday, December 22, 2018

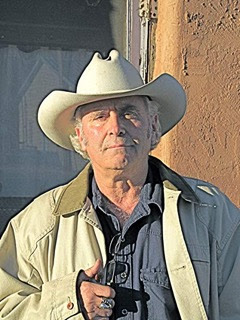

Tommy Mac and Beckett plus

Ace big game hunter Tommy McIntyre (who is disturbed about Burkina Faso the way I am about Turkish Kurdistan , for the same reason and with about as much effect), has been healing his soul by dabbling (I hope he forgives the verb) in Beckett. Here he is in Endgame

I thought he might like to see my personal Beckett photo, taken by my friend Michigan fisherman and artist Dellas Henke, in Paris of course -- that's him with Beckett.

The last pic is us at our first meeting in our heedless youth, in the North Plains of Catron County.Time is not kind.

I thought he might like to see my personal Beckett photo, taken by my friend Michigan fisherman and artist Dellas Henke, in Paris of course -- that's him with Beckett.

The last pic is us at our first meeting in our heedless youth, in the North Plains of Catron County.Time is not kind.

Thursday, December 20, 2018

The Illustrious Cripple, the late Bill Wise (so self -described ) amidst haunts and passions...

Bill broke a vertebra surfing with Hobie Alter at 26 and forgot to pay attention. He lived and adventured, shot deer and geese, sailed, collected guns, and built up a wise portfolio. He died at 56 from complications from his quadrieplegia, and left no stone unturned.

More :

More :

Thursday, December 06, 2018

Bob French, RIP

One of my oldest and best friends, Roberts French, died in Santa Fe a few days ago. I believe he was 84. He survived a year longer than the docs gave him, but the cancer finally wore him down.

When I first met Bob and Jenny, in the early seventies at U Mass, Amherst, he was a young English prof and I an eccentric older student. (Jenny was even then a serious painter, as she still is).We soon both found ourselves on the board of English Literary Renaissance, a job for which I was not even remotely qualified for. Nevertheless, under the guidance of Arthur Kinney and Bob I became a somewhat competent nuts and bolts editor. The high point of my job was asking Philip Larkin to write something for our Marvell anniversary edition. (They had both been librarian of Hull). He was perfectly pleasant and wrote us an essay, but as I said to Bob many times, if I had known of his reputation I would not have dared to call him.

Bob was the only other ourdoorsman on the staff -- a flyfisher and mountaineer, thus we gravitated toward each other. When he showed me some wonderful fishing poems he had written, I immediately bought them for Gray's Sporting Journal for more money than poems were going for then.This gave rise to a comedy routine which we performed to the end of his days. I would say "I bought Bob's first poem"; he would say "No, you didn't.You bought my second and third poem. My first went to an academic review for seventy-five cents; then you bought the second and third for five hundred dollars."

Improbably, when I first started seeing Libby, she had a friend named Muffy Corbet Moore in Wyoming, who turned out to be Bob's sister. Bob and Jenny had retired to Santa Fe and very shortly became our best friends in Santa Fe and virtually in the state. They brought provisions to Libby's mother's funeral where we were stressed by being the only family members present because of the suddenness of the death. Bob and Jenny always knew the right things to do. Sometime I'll tell here what she said to my mother after taking that mad woman over for three days during Jackson and Niki's wedding celebration. Suffice to say now, it reduced my mother to horror and laughter at the same time. Today, with Bob barely gone, Jenny was worried about getting a chair I could sleep in down to Magdalena. Need I say that I love these people?

A colleague wrote of him: "To me, Bob French epitomized the best of the academic profession. He genuinely cared -- about everything and everybody. I kept hearing how his students worshipped him; he was an ideal colleague; whenever things got tough at UMass, and they often did in those early building years, there was Bob, shoulder to the wheel. Roberts W. French led an exemplary life from which we can all learn. I am diminished and profoundly saddened at his loss."

Here are the poems that I bought:

BOB BAGG FISHING

He stands waist-deep in swirling waters,

brooding, brooding...

when he casts his line, he shapes the sky;

clouds are formed to new precisions,

and light is flashed to sudden brightness.

When he drops his line upon the waters,it falls

as gentle as a hand on shining hair.

He gathers the river around him,

he draws the mountains into a circle.

The trees and rocks lean forward

to see him fishing, fishing.

DON JUNKINS FISHING

Junkins dropped a glob of worms

over the side. They're here,

he said. You wait. He rolled

about his beard a bright cigar.

I waited. Junkins beat his worms

upon the waters These goddam fish,

he said. I just don't trust them,

not at all. I just don't trust them,

Junkins said.

Quote

"Writers are usually embarrassed when other writers start to “sing”–their profession’s prestige is at stake and the blabbermouths are likely to have the whole wretched truth beat out of them, that they are an ignorant, hysterically egotistical, shamelessly toadying, envious lot who would do almost anything in the world–even write a novel–to avoid an honest day’s work or escape a human responsibility. Any writer tempted to open his trap in public lets the news out"

Dawn Powell, Diaries. Thanks to Tommy McIntyre

Dawn Powell, Diaries. Thanks to Tommy McIntyre

Saturday, November 10, 2018

Walter Becker, RIP

Walter Becker slipped away last year, causing barely a ripple in the media. He was half of the writing team of Steely Dan, along with the more forward Donald Fagen, since their days together at Bard College. Their music defined my 1970s,along with that of many of us who were more cerebral than, say, Eagles fans. It is said that they wrote the charts for every so-called solo that their "band" (which also needs to be put in quotes because they never were a band) played. This drove some of the better musicians associated with them, like Jeff "Skunk" Baxter, nuts, but he returned again and again. It was perhaps typical of the hipness and oddness of the Dan of steel that Baxter became a national security expert after 9-11, and was responsible for catching many terrorists, though he still looks like a California hippie and still plays occasionally with the big band, the current incarnation of Steely Dan.

Since Bard days, Steely Dan was really only two people, Donald Fagen and Walter Becker, with the entire American jazz and pop songbook in their heads (listen to their arrangement of Duke Ellington's "East St Louis Toodle-Doo"), and what some say was darkness in their hearts. Jay of Jay and The Americans, who used them as a backup band in days gone by, called them Manson and Starkweather. A critic at, I believe, Time, called them The Grateful Dead of Bad Vibes, showing an almost willful contempt for and ignorance about both the Dead and the Dan. But despite the fact that they were named after a dildo in a William S Burroughs novel and occasionally wrote about mass murderers and cheating gamblers, the most typical Dan hero was a failed romantic, a loser of some essential thing, a melancholic and a stoic, living as best he could. From the Midnight Cruiser on the first album ("I am another gentleman loser...") through the fellow who until his ship comes in lives "Night by Night" to Deacon Blues, to besotted lovers pursuing pornstars, old men in love with unsuitably young women, the entire populace of Puerto Rico (The Royal Scam) and the fool begging Rikki not to lose his number in what must the beautiful song about a deluded lover ever written, all of Becker and Fagen's heroes come at last to a worn door in an Asian (or universal? after all, "Klaus and the Rooster", who sound like Euro- trash mercenaries, are also patrons) bar and whorehouse where they "knock twice, rap with their canes" to find a kind of false peace and security that may be the only kind that exists, here at the Western World.

Such realism is not usually the province of rock bands, nor such musicianship; nor, for that matter, so much submersion of the ego to the music. Walter Becker, the more self- effacing of the pair, died in Maui months ago, and I didn't even find out until last week. That I am still playing their songbook almost weekly, when they closed entirely in 1980 but for rare big band tours doing "archival" material, is a tribute to the quality of the music they made.

With Baxter, recently

Since Bard days, Steely Dan was really only two people, Donald Fagen and Walter Becker, with the entire American jazz and pop songbook in their heads (listen to their arrangement of Duke Ellington's "East St Louis Toodle-Doo"), and what some say was darkness in their hearts. Jay of Jay and The Americans, who used them as a backup band in days gone by, called them Manson and Starkweather. A critic at, I believe, Time, called them The Grateful Dead of Bad Vibes, showing an almost willful contempt for and ignorance about both the Dead and the Dan. But despite the fact that they were named after a dildo in a William S Burroughs novel and occasionally wrote about mass murderers and cheating gamblers, the most typical Dan hero was a failed romantic, a loser of some essential thing, a melancholic and a stoic, living as best he could. From the Midnight Cruiser on the first album ("I am another gentleman loser...") through the fellow who until his ship comes in lives "Night by Night" to Deacon Blues, to besotted lovers pursuing pornstars, old men in love with unsuitably young women, the entire populace of Puerto Rico (The Royal Scam) and the fool begging Rikki not to lose his number in what must the beautiful song about a deluded lover ever written, all of Becker and Fagen's heroes come at last to a worn door in an Asian (or universal? after all, "Klaus and the Rooster", who sound like Euro- trash mercenaries, are also patrons) bar and whorehouse where they "knock twice, rap with their canes" to find a kind of false peace and security that may be the only kind that exists, here at the Western World.

Such realism is not usually the province of rock bands, nor such musicianship; nor, for that matter, so much submersion of the ego to the music. Walter Becker, the more self- effacing of the pair, died in Maui months ago, and I didn't even find out until last week. That I am still playing their songbook almost weekly, when they closed entirely in 1980 but for rare big band tours doing "archival" material, is a tribute to the quality of the music they made.

With Baxter, recently

Friday, November 09, 2018

Inspiration

I am proud to be published by Karen Myers' Perkunas Press, and even prouder to be the first writer in her Beyond The Ridges imprint. Karen chose her title well. Kipling was my first and is finally my favorite writer; as he wrote about "Janeites", obsessive fans of Jane Austen, so I am "Rudyardite", with a love for strange trails. I have asked Libby to have the following lines, from "The Song of the Dead", chiseled on my grave:

We were dreamers, dreaming greatly, in the man-stifled town;

We yearned beyond the sky-line where the strange roads go down...

But the imprint is from another poem, The Explorer:

"There's no sense in going further— it’s the edge of cultivation,”

So they said, and I believed it—broke my land and sowed my crop—

Built my barns and strung my fences in the little border station

Tucked away below the foothills where the trails run out and stop.

Till a voice, as bad as Conscience, rang interminable changes 5

On one everlasting Whisper day and night repeated—so:

“Something hidden. Go and find it. Go and look behind the Ranges—

“Something lost behind the Ranges. Lost and waiting for you. Go!”

So I went, worn out of patience; never told my nearest neighbours—

Stole away with pack and ponies—left ’em drinking in the town; 10

And the faith that moveth mountains didn’t seem to help my labours

As I faced the sheer main-ranges, whipping up and leading down.

March by march I puzzled through ’em, turning flanks and dodging shoulders,

Hurried on in hope of water, headed back for lack of grass;

Till I camped above the tree-line—drifted snow and naked boulders— 15

Felt free air astir to windward—knew I’d stumbled on the Pass.

’Thought to name it for the finder: but that night the Norther found me—

Froze and killed the plains-bred ponies; so I called the camp Despair

(It’s the Railway Gap to-day, though). Then my Whisper waked to hound me:—

“Something lost behind the Ranges. Over yonder! Go you there!"

There is more....

We were dreamers, dreaming greatly, in the man-stifled town;

We yearned beyond the sky-line where the strange roads go down...

But the imprint is from another poem, The Explorer:

"There's no sense in going further— it’s the edge of cultivation,”

So they said, and I believed it—broke my land and sowed my crop—

Built my barns and strung my fences in the little border station

Tucked away below the foothills where the trails run out and stop.

Till a voice, as bad as Conscience, rang interminable changes 5

On one everlasting Whisper day and night repeated—so:

“Something hidden. Go and find it. Go and look behind the Ranges—

“Something lost behind the Ranges. Lost and waiting for you. Go!”

So I went, worn out of patience; never told my nearest neighbours—

Stole away with pack and ponies—left ’em drinking in the town; 10

And the faith that moveth mountains didn’t seem to help my labours

As I faced the sheer main-ranges, whipping up and leading down.

March by march I puzzled through ’em, turning flanks and dodging shoulders,

Hurried on in hope of water, headed back for lack of grass;

Till I camped above the tree-line—drifted snow and naked boulders— 15

Felt free air astir to windward—knew I’d stumbled on the Pass.

’Thought to name it for the finder: but that night the Norther found me—

Froze and killed the plains-bred ponies; so I called the camp Despair

(It’s the Railway Gap to-day, though). Then my Whisper waked to hound me:—

“Something lost behind the Ranges. Over yonder! Go you there!"

There is more....

Thursday, November 08, 2018

Bird

He looks pretty relaxed these days. Now to find him some quarry....

The next is from another life, forty- some years ago, when I lived in the January Hills, ate roadkill, and edited a journal of Renaissance studies. That's Cinammon, one of the two best hawks I have ever had, stolen from me not once but twice.

The next is from another life, forty- some years ago, when I lived in the January Hills, ate roadkill, and edited a journal of Renaissance studies. That's Cinammon, one of the two best hawks I have ever had, stolen from me not once but twice.

It's a book!

Tiger Country is available from the publisher, in various format at https://behindtherangespress.com/books/tiger-country/".

.. and from Amazon here at https://www.amazon.com/dp/B07JYT29CK

Some good people have said nice things about it. Malcolm Brooks, the hyper- literate author of Painted Horses, says: "Steve Bodio brings his legendary Renaissance vision to this startling first novel, a work so mammoth in scope and elegant in execution it makes me wish he’d been writing fiction all along. Recalling the edgy best of Ed Abbey and Jim Harrison, and reminiscent of James Carlos Blake’s contemporary border noir, Tiger Country throws modern heroic renegades into the gravitational pull of the ancient past, to encounter the origins of the human condition. Though it makes admirable use of the techniques of the modern thriller, this book nonetheless has its roots in the classical literary tradition, populated by fascinating, unpredictable characters asking dangerous questions about the world we inhabit. Gripping, and utterly one-of-a-kind."

John Barsness, native Montanan and poet turned firearms maven and proprietor of The Rifle Looney News, says: "Steve Bodio chose New Mexico as the surrounding essence of his life decades ago--or perhaps New Mexico chose him. Tiger Country is a well-told tale of the many human conflicts of the New West, both philosophical and physical, by one of the best "nature" writers of his generation, because he knows humans are part of the natural world, whether for good or evil.

Cat Urbigkit, public- land pastoralist and expert on the brave dogs who sometimes give up their lives for their herds, whose next book is on (NOT against!)the grizzly in the greater Yellowstone region, says: "No one better articulates the natural history of the desert southwest's wildlands than Steve Bodio. His first novel incorporates vivid and raw human and animal characters, while skillfully blending mixes of culture, blood sport, and landscape."

Tom McIntyre is either the most literate of hunting writers or the most serious hunter among literary writers. He went to Reed College and since then has mostly hunted and written hundreds of articles and more books than I can easily count, including my favorite, the Asian fantasy The Snow Leopard's Tale and, most recently, Augusts in Africa. He lives in Sheridan Wyoming, whence he writes: "Tiger country” by definition is where you tread with care, a land of risk and danger. A labor of many years, much sharp observation, depths of creative imagination, and a life of his own lived on the outermost rim of the most extreme Southwestern geography, Stephen Bodio’s Tiger Country presents a fell vision of rewilding, brought forth in writing that is nothing less than rewilded itself. You can only feel alert as you venture through it."

Sy Montgomery, the only committed vegetarian I know who has trained a hawk to hunt, has also walked across Mongolia, lived in the man-eater infested Sunderbans on a houseboat where all the tigers swim, and made friends with a pig and an octopus. She lives in New Hampshire with her husband Howard and, until recently, a wise old border collie, who she still mourns: "Tiger Country is ferociously hones and true."

Elizabeth Marshall Thomas should have been a conventional young lady. But her father took her to Botswana to live with the Bushmen for several years and her life was permanently changed. She has written extensively about them, as well as novels about ancient hunter-gatherers and their spirit. She kept a free range pack of dogs in Cambridge who did very well. She may be the wisest woman I know, and certainly the most observant. She said "No book should be the same as any other book, but this one is so unusual it could set a new standard. It's a compelling, fascinating story written by a man who knows what he's talking about."

I respect the opinions of these people, and I hope you do. Won't you check it out?

There will be much discussion in future posts of this blog and the new one, which I hope will be up soon. Stay tuned...

.. and from Amazon here at https://www.amazon.com/dp/B07JYT29CK

Some good people have said nice things about it. Malcolm Brooks, the hyper- literate author of Painted Horses, says: "Steve Bodio brings his legendary Renaissance vision to this startling first novel, a work so mammoth in scope and elegant in execution it makes me wish he’d been writing fiction all along. Recalling the edgy best of Ed Abbey and Jim Harrison, and reminiscent of James Carlos Blake’s contemporary border noir, Tiger Country throws modern heroic renegades into the gravitational pull of the ancient past, to encounter the origins of the human condition. Though it makes admirable use of the techniques of the modern thriller, this book nonetheless has its roots in the classical literary tradition, populated by fascinating, unpredictable characters asking dangerous questions about the world we inhabit. Gripping, and utterly one-of-a-kind."

John Barsness, native Montanan and poet turned firearms maven and proprietor of The Rifle Looney News, says: "Steve Bodio chose New Mexico as the surrounding essence of his life decades ago--or perhaps New Mexico chose him. Tiger Country is a well-told tale of the many human conflicts of the New West, both philosophical and physical, by one of the best "nature" writers of his generation, because he knows humans are part of the natural world, whether for good or evil.

Cat Urbigkit, public- land pastoralist and expert on the brave dogs who sometimes give up their lives for their herds, whose next book is on (NOT against!)the grizzly in the greater Yellowstone region, says: "No one better articulates the natural history of the desert southwest's wildlands than Steve Bodio. His first novel incorporates vivid and raw human and animal characters, while skillfully blending mixes of culture, blood sport, and landscape."

Tom McIntyre is either the most literate of hunting writers or the most serious hunter among literary writers. He went to Reed College and since then has mostly hunted and written hundreds of articles and more books than I can easily count, including my favorite, the Asian fantasy The Snow Leopard's Tale and, most recently, Augusts in Africa. He lives in Sheridan Wyoming, whence he writes: "Tiger country” by definition is where you tread with care, a land of risk and danger. A labor of many years, much sharp observation, depths of creative imagination, and a life of his own lived on the outermost rim of the most extreme Southwestern geography, Stephen Bodio’s Tiger Country presents a fell vision of rewilding, brought forth in writing that is nothing less than rewilded itself. You can only feel alert as you venture through it."

Sy Montgomery, the only committed vegetarian I know who has trained a hawk to hunt, has also walked across Mongolia, lived in the man-eater infested Sunderbans on a houseboat where all the tigers swim, and made friends with a pig and an octopus. She lives in New Hampshire with her husband Howard and, until recently, a wise old border collie, who she still mourns: "Tiger Country is ferociously hones and true."

Elizabeth Marshall Thomas should have been a conventional young lady. But her father took her to Botswana to live with the Bushmen for several years and her life was permanently changed. She has written extensively about them, as well as novels about ancient hunter-gatherers and their spirit. She kept a free range pack of dogs in Cambridge who did very well. She may be the wisest woman I know, and certainly the most observant. She said "No book should be the same as any other book, but this one is so unusual it could set a new standard. It's a compelling, fascinating story written by a man who knows what he's talking about."

I respect the opinions of these people, and I hope you do. Won't you check it out?

There will be much discussion in future posts of this blog and the new one, which I hope will be up soon. Stay tuned...

Wednesday, October 31, 2018

Quote

"The land was not to blame. It was up to the individual to decide whether to live here or not..."

Chingiz Aitmatov

Chingiz Aitmatov

Saturday, October 27, 2018

Monday, October 22, 2018

The Hawk

Until last week he was rhe worst hawk I have ever owned, the worst hawk in the world, a complete malimprint, the only one i have ever owned save a crazy redtail in 1967. My first wife Bronwen Fullington reminded me of him when I told her of this one; she well remembered the time she retrieved Loki from the top of a tall white pine, dressed only in her nightgown and with no glove, despite the damage he caused. At the time I thought it esperately sexy...

"Hauksbee" was as bad or worse if a little smaller (not too much- he flies just under 600g) He screamed from dawn to dusk, leaped off the lure or perch to attack human or dog, mantled constantly, broke tailfeathers, fought the hood,the whole litany.I ascribed this to his being too old when he came to me, but he was intolerable.In disgust, I put him out in the yard mews and left him alone,,feeding him through a chute.

In three days he did something I've never seen in my life, in fifty- eight years of falconry: he trained himself into being a good bird without any vices all by himself. I've now flown him for a week on the creance, and he's ready to fly by himself. No screaming, no mantling; he even takes tidbits delicately from my fingers when he steps off the hare lure. Believe it? I didn't either, but look at the pictures. He also eats his quail meal on the round perch in the kitchen with all the dogs and people around him and doesn't mantle then either.

Oh and-- congratulations to Lauren McGough for making the case for falconry to a large audience in her excellent 60 Minutes segment last night.

"Hauksbee" was as bad or worse if a little smaller (not too much- he flies just under 600g) He screamed from dawn to dusk, leaped off the lure or perch to attack human or dog, mantled constantly, broke tailfeathers, fought the hood,the whole litany.I ascribed this to his being too old when he came to me, but he was intolerable.In disgust, I put him out in the yard mews and left him alone,,feeding him through a chute.

In three days he did something I've never seen in my life, in fifty- eight years of falconry: he trained himself into being a good bird without any vices all by himself. I've now flown him for a week on the creance, and he's ready to fly by himself. No screaming, no mantling; he even takes tidbits delicately from my fingers when he steps off the hare lure. Believe it? I didn't either, but look at the pictures. He also eats his quail meal on the round perch in the kitchen with all the dogs and people around him and doesn't mantle then either.

Oh and-- congratulations to Lauren McGough for making the case for falconry to a large audience in her excellent 60 Minutes segment last night.

Sunday, October 21, 2018

The Artist's Son: for my Father

A version of this appeared in Anglers last year, but in a low- toned gentle version that made my Dad simply a sad nice guy.

Fact is, Joe Bodio was not a sad nice guy. He was a passionate conflicted sometimes brilliant guy who first taught me to love his passions- fishing, hunting, art-- and when he succeeded, seemed to turn against them and me for thirty years. Not a nice guy at all. This is the story of a difficult man's redemption, and it is interesting mainly because of that.

I know, because I am the artist's son. This is the first time the whole story has ever been published.

Illos too!

Predestination...

Striper hipster

At around the age of thirty, an observation by Elizabeth Katherine Huntington that I was “an artist with nice guns” struck me with unexpected force. I realized that I had become a man my father always wanted to be. And that he hated it. I was an artist only in the broadest sense, a sportsman with a madness that has a little to do with ability and a lot to do with obsession, successful only in the smallest of subcultures, but had my very successful father ever wanted to be anything else?

******

See: in the early 1950’s, a very young man in a three-story Dorchester walk-up, a first generation American born to immigrants from the Swiss border fueled by passion and talent, married to a pretty young woman of a different class and ethnic background, with nothing to show but those passions. At that time he really was an artist: a painter a sketcher a sometime sculptor – and a man with a passion for animals, fish, birds, mammals, their shapes and sizes and feathers and movements. In a dingy blue-collar neighborhood, all my early memories are of animals, alive and dead dirt-common and exotic. All before I was five, because of their context; black gas stove with blue and gold flickering flames, basement coal chute, blacker than black, dust on your hands, there stories, white-fenced porches on each level. Its only existence is in a few molecular memories—Google Earth shows the very street vanished below the obliterating white geometry of Ashmont Station.

Against this faded dream: a flash of the most intense blue I have ever seen, edged as for emphasis with black and white. It is the shimmering speculum of a “Black mallard” – Yankee for Black duck – which he takes from the pouch in the back of his coat one morning followed by three more. I am mildly confused because it is NOT black but a rich chocolatey brown. I already know my colors. At four, how would the artists’ son know? My father works as an “engineer”, which I don’t understand because in my mind an engineer drives trains. But not long-ago Dad was a “scholarship student at the Museum School”. And Mum was a commercial artist, drawing models in furs for Kakas of Newbury Street. The relic of which is another fascinating animal, a full-length ocelot coat.

But the ducks…like other beings soon to come, the ruffed grouse, the flounders, the stripers, the brookies, the hornpout, the yellow perch, the mackerel and soon, the tuna and the white-tailed deer, they were all I could focus on as long as they were visibly themselves. And then they became holy relics. I kept those feathers for a decade.

My father let me carry it to the table. That it was dead did not bother me. The only live animals I knew were English sparrows, pigeons high overhead, as remote as angels, and the ragman’s blinkered horses. I had found a dead mouse in the bedside water glass, a dead pigeon in the yard covered by live ants, my cousin’s dead cat, Snoozy smashed in front of my house on Templeton Street. It might be human nature, or something genetic in the artist’s boy, or a little of both, but I found them far more interesting than my little metal plane with the rotating blue propellers, or my toy trucks, maybe an undiagnosed case of Biophilia, not yet invented by Ed Wilson but already hinted at by Aldo Leopold: “…the man who does not like to see, hunt, photograph, or otherwise outwit birds or animals is hardly normal. He is super civilized, and I for one do not know how to deal with him. Babies do not tremble when they are shown a golf ball, but I should not like to own the boy whose head does not lift his hat when he sees his first deer.”

So: dead heavy, limp, wet feathers shimmering like watered silk when I stroked against the grain, deep and thick and soft against it. I could have handled them for hours, but Dad had something else in mind.

He set them gently on the table or rather on the newspapers my mother had provided set one on its back and stripped off a couple of big chunks of feathers against the grain. He smoothed them out in his palm to reveal a single feather, crossbarred with light pencil lines. “I’ll teach you how to tie flies”, he said. “These are the feathers that make wings for flies.” Perhaps he saw the incomprehension in my eyes because he grinned. “Flies – to catch fish. Trout.” He went out, put the feathers down, and came back with a shiny silver box. When he pointed out the wings I could see they were the same as the ones we’d taken from the dead bird. Do artists, or artists’ kids, imprint like birds? Sixty some years later I’m still dazzled by the treasure he revealed in that box. And I still have it, and a few flies I’ll never fish.

The next event in our lives brought us much closer to fish and birds and nature and game. In 1954, we moved to what my mother considered wilderness. These days with Easton a crowded bedroom community located rather less than twenty miles south of downtown Boston, this would seem ludicrous. But in those days, my urban maritime mother wasn’t far off. Easton still had dirt roads, and its population of Yankees, rich and poor, and ethnic Portuguese looked not to Boston but to New Bedford and Taunton to the south, to cranberry bogs and whaling towns. Not a few of the oldsters there had never been to Boston and had no intention of going. To me the raw subdivision hacked into the fringes of a boggy seasonal swamp was a paradise for a novice hunter – gatherer. For our first two years, our basement had six inches of water and three species of calling frogs in it. To me, in today’s vernacular it was a feature, not a bug; not the result of a cynical ploy to fleece the World War II generation, but a habitat.

Dad eventually put in a pump and got rid of the frogs, but I don’t think he was bothered by them. He ramped up his leisure time activity even as I filled my jars with frog spawn, and often took me with him. It was around this time that I caught my first trout in his company, in what was then known as the Blue Hill River. In 1955 it still contained native brook trout, and again the artist’s eye rewards me. My father had been fishing a cast of wet flies, something that he did so often then that a part of my brain still considers it the only way to go. After a while he sat down on a rock and asked me if I would like to catch a trout. He was always a fisherman whose artistic purity fought his dogged north Italian pragmatism but right now neither seemed relevant. He took a coffee can out of his box and hooked a squiggle worm on to, if I remember, one of the flies. “They like these better”. He rolled the line lightly upstream and put the rod in my hands, stripped line for me, and then raised the rod tip, which began to dance. “You’ve got him! Reel him in.” He actually grabbed my little hand and whirled it around the reel as he backed up until it skittered on to the bank. “you’ve got him!”

I did have him. He was probably five inches long, but the red and white in his fins and the mottled vermiculations of his back glow in my memory as the most beautiful fish I have ever seen. That night we ate him fried in butter. Need I say that I still do that?

Today, I’m sure the Blue Hill River exists. Last I checked, it was a trickling culvert under what was then Route 128, now a part of I-95, neither of which were built when I caught my trout. But such tiny natives were always an almost invisible reward for those who shunned more popular quarry. They may be gone from the Blue Hills, but my friend and contemporary Paul Dinolo, a retired teacher, still catches, releases, and occasionally eats my trout’s close relatives in the numerous dark cedar bogs of Plymouth County .

The next fish I remember remains at the opposite end of the scale. I did not see it caught, off Chatham, in my father’s deep-sea saltwater phase, but discovered it beached in the shingle, waiting to be cleaned. For no reason an adult can fathom, my first reaction, and my little bother Mark's, was to take off our shoes and WALK on them.

Maybe it was just a wordless testimony to their size. Although they were all what we would soon learn to call "just little schoolies", weighing no more than 100 pounds, most less than 50.They were the biggest fish we'd ever seen. In retrospect, they were probably the biggest my father had ever seen, which explains why his reaction was to beam at us, rather than to snap at us, "Get off the fish", which would have been more in character.

It was probably the beginning of what was the most idyllic period of our sporting relationship. There is something sweet about teaching a child to fish especially if all the material, from bait to quarry, is near to hand. We had Knapp's pond, now a eutrophicated "wet meadow" but then a gloriously productive pond with three species of game fish broadly defined; no, actually more than that. There were three species of sunfish alone, including big bluegills, an edible spiny catfish which most people today call black bullhead but which we called hornpout, and sinister but elegant chain pickeral. Not to mention a diverse herpetofauna including many snakes and more amphibians which interested my dad as well, though not the rest of the family -- another little bond. My father was always a naturalist.

I had my own spinning outfit by then. I don't remember a thing about it. What I remember is my father. He fished with the most beautiful spinning reel I’ve seen before or since: an Alcedo Micron. It was a color of pewter and had a kingfisher in raised relief on the side. I coveted it as I have come to covet all too many kinds of fine tackle. Perhaps a writer’s appetite for words started with the names of equipment, the “lyricism of shoptalk” as Thomas McGuane had it. Names to say, names to covet: Alcedo, Penn, Browning, Winchester, Pfleuger, Hardy Orivs, Leonard…

On Knapp’s Pond we would take our separate perches usually on opposite sides of the little dam that emptied beneath the road, and make our own choices of bait or lure. At that time, Dad would only suggest if the fishing seemed slow. He favored sunfish and hornpouts both quite edible, even acceptable to my mother I liked the hornpout because they could hurt you and with their sharp spines in their pectoral fins, and my father had showed me how not to get hurt. Mastery of even a simple skill encourages you to learn more. But really, I preferred pickerel, which we didn’t eat. “Too Goddamn bony!” I didn’t care. When one came in, slashing its snaky body across the lily pads, with its golden chain pattern and barracuda teeth, I was in ecstasy. I didn’t even mind cutting it loose, and in those days, like most kids, I wanted to keep everything. My response was a combination of adrenaline and esthetics. Ted Hughes was soon to write his poem “Pike”, about the pickerel’s bigger relative:

“Pike, three inches long, perfect.

Pike in all parts, green tigering the gold.

Killers from the egg: the malevolent aged grin.

They dance on the surface among the flies.”

The last form of fishing I was exposed to in the 50s has been a lasting source of fascination for me though I never was able to combine the time the place, and the culture to hit it just right. The mid-50s were, I think the first period of serious surfcasting for stripers and blues. The photos make me ache with nostalgia: ancient woodies with rod holders on their front bumpers rolling down the beach at Chatham or Duxbury with waves crashing beside them; all those World War II veterans with big casting rods and casting reels like the Penn Squidder. The preferred lure was the “tin squid”. I haven’t seen one in decades, but its soft luster and texture, its heft, its ability to take a shine when you rubbed it in the fine sand, was like nothing else I have touched before or since, like a nobler form of lead. The other think I remember my father using was the eel skin rig. On my last stab at seaside life, in the 70s, I did try this, but those years were in the lull between the two great explosions of big stripers, and I never caught much.

As I was learning all this from my father, I was also learning it from, Field and Stream and all the other old-fashioned sporting magazines. And books. My mother’s contribution to making me a worthless lay about was teaching me how to read – family legend says at three. This is more than possible. At three my mother was reading Kipling aloud to me, as well as everything about animals in every publication in the house’ and sounding out the words for me. As I tested out at an eight-grade level reading before my sixth birthday, doing stunts like reciting the scientific names in Peterson’s bird guide to a nun with a PhD in psychology, this timeline is likely true. What I read about was live things – natural history, field guides, tackle articles, the “Old Man and the Boy” from Field and Stream, William Beebe’s books about tropical reefs, Adrian Conan Doyle’s tales of manta rays and killer sharks were all fodder for my imagination. I’m just as bad at 65.

Meanwhile, something was happening to my father; something in retrospect, sad though I found it disturbing. He wasn’t spending much time doing interesting things. His temper – he was never serene – was getting shorter and shorter. I wanted to hunt was well as fish but after a few sessions with him bird hunting, I retreated. When I learned to fish I watched him, and received advice when I asked for it. Bird hunting was different. First, we had no dog. His big-going Texas English pointer Joe, who could be the subject for another article, was unsuitable for New England hunting, and had died of old age. Dad’s method now was to march around grumpily in grouse cover with his sweet sixteen Belgian Browning, while I carried a rather heavy single-shot .410 choked tighter than a gnat’s butt. He insisted I shoot first, and when I did and missed he would snap me on the back of the head and refuse to allow me to reload, saying “watch what I do.” He would then either shoot a grouse, after which we would go home, or not shoot one and be in a bad mood that I had blown our opportunity. He employed the same methods to teach everything from fly-tying to driving a stick shift and I learned to teach myself.

As he rose in his company and worked more hours and more, he did less fishing and hunting even as I became obsessed with it. On the occasions that he did, all its fruits went to my grandparents in Milton. My grandparents had a rather incredible lot there with twelve apple trees, a grape arbor and a garden larger than the one I cultivate today in New Mexico. They also kept “anything that doesn’t make a noise” i.e., rabbits and pigeons as opposed to ducks and chickens. They made grape wine and dandelion wine, picked dandelions and wild mushrooms, baked their own bread, and killed sparrows in the pigeon loft to make sauce for polenta.

My mother was overwhelmed by much of this though grateful that they took the game off our hands. More disturbingly, my father – or Joe – as we kids were coming to call him as he distanced himself from what he loved, and I think, from us, had no time for the food of his roots either. Just a few years before he was the only man besides my grandfather who cooked; now if he could not get to the Bodios, we ate 50s food. The pattern was set: Joe worked, I became ever more obsessed with fishing, hunting nature, animals, and books. Though a scholarship student all through my grammar and prep school years, my grades were indifferent. When I wanted to use one of the rods or guns, I had to undergo a grilling. “Why are you wasting your Goddamn time?” was a constant refrain. He sold the best gun he ever had, an early Model 21 Winchester with two triggers; his better cane rod and the Alcedo and the Hardy disappeared; even the racing pigeons which he imported from France, bred and studied and raced, another bit of biophilia I came to inherit, were first ignored and then abandoned. Looking back, I think they were a last attempt at having some contact with nature without having to take up any time traveling. When I left home prematurely at seventeen, blown along by the raging winds of the 60s, we were barely talking.

And so it remained for a decade; no I am whitewashing; it got worse. During these years, whether in an apartment in Cambridge, a fishing shack in Canton, an 18th century farmhouse in Shutesbury, or a relative’s rental in Marshfield, I devoted my life to fishing and hunting and writing and nothing else of practicality. When in 1970 he told me to take my wife and my dog, in that order and get off of his property, I didn’t talk to him for two years. When a few years later, slightly reconciled, I brought a 28-gauge AyA sidelock to his office, brimming with pride at my brilliant taste, he turned to his lackey and said “Look at this John. My asshole son just bought a rich man’s gun.” That he had recently sold a Winchester worth five times as much was not something I felt able to say, I just walked out and didn’t talk to him again for two years.

The genuinely funny part of all this is that our period of greatest estrangement was when I approached the ideal of the life he had taught me. My years in Green Harbor just yards from Duxbury Marsh, were the high point of my fishing-hunting-eating career. No place in New Mexico or the Rocky Mountains could sustain such a prolonged feast. In those days, my friends and I fished and gathered year-round, and hunted whenever we could. We threw clam baits to cod in the winter surf, fished for stripers and blues on the jetties and off Duxbury bridge, where we also caught flounder and eels, free-dived for lobsters before that was considered attempted theft; we gathered quahogs and steamers and sometimes razor clams; we ate blue mussels steamed in game broth or wine before the restaurants discovered them – “You eat those blue things?” In the fall Black ducks and Brant were among the commonest quarries on the marsh, still two of the best eating birds I know; woodcock and grouse were not far away in remnant patches of forest; I even learned how to cook the scoters and eiders that fell to my 10 gauge when I anchored my battered boat in the winter surf; if you cube the meat and put it in buttermilk overnight you can make a hearty chowder that everyone loves. Just a little further afield, in the tiny streams of the south Cape, we discovered salters, native sea-run brookies seemingly unknown to anyone but us and our close friends. A few of these streams still had clean oysters.

But I still wasn’t talking to Joe. When I moved out to western Massachusetts to polish my skills as a writer, we had a rather tentative rapprochement. When I heard he was attending a business conference in the valley I invited him and my mother to dinner at my house Was it perversity that made me serve them a Brunswick stew made from road-kill squirrel? Which, miraculously, Joe loved, though my mother took some persuading. Still we remained wary. He looked around at the old wood-heated house and said, “You really think you can make a living from this?”

Several years later, I was doing just that with the steadfast encouragement of Elizabeth Katharine Huntington, a partner who believed in the life that I lived. She had a legendary background, had money when she was young, blew it, put herself through BU Journalism School by waitressing, and never complained. She had been everywhere and had done everything and was startlingly frank. Improbably, she hit it off with Joe, the first of my partners ever to do so. It was all the funnier because he, whose precarious prosperity was earned by a typical first-generation ethic of hard labor, tended to call Yankees with broad vowels “Inbred overbites”. To which Betsy would amiably agree. “That’s all right Joe. The Huntingtons and Trumbulls are just Connecticut Valley farmers who said ‘ain’t’ until the 1950s”.

And she cracked a mystery. One night she asked him flat-out why he had given up art, and fishing and hunting, and seemingly, fun.

We were on our third or fourth Jack Daniel’s. he said “Betsy, when I came back from the war, it was a little early because I had flown thirty-four missions. I had big ideas. I’d done my flight training in Roswell, New Mexico, and hunted with a rancher there who had promised me a dog. He sent me the dog on the train. I had bought an antique Cadillac roadster, and rode off to Roxbury to show my old man what a swell guy I was”.

“I drove up and knocked on the door, and Rico came out and looked at me and said “Get your Goddamn rich man’s dog and your Goddamn rich man’s car off my lawn.”

“I didn’t care. I had survived the war, I was a scholarship student and I had talent. In England, as a first lieutenant, I was an officer and a gentleman. I rented a studio with the two most talented artists I know. One was a veteran, and one day they carted him off, screaming. He had what they called “battle fatigue” in those days.”

“Then I started watching my other friend and realized that he was gay. My father had been nagging me constantly and was always saying that all artists were either crazy or queer. I was doing some good work, but I didn’t know how to sell it and my money was running out. All of a sudden I got scared. I sold all my stuff and applied to Carnegie Mellon, and the rest is history. I started in a company and ended up owning it, and as you know I lot a good bit of it in the last crash.”

“I did it all for security and, you, know, I did it wrong. I’ve harassed this Goddamn kid for thirty years, and you know what? He made the right choice. There is no Goddamn security.”

And he looked me in the eye and clinked his glass on mine.

I never had an argument with him again. He came to New Mexico; we took him to rodeos, we went birding, we fed him wild things. He called Betsy in the hospital in her last week, and I managed to see him just before his. He might not have attained security but he had some measure of serenity. I have very little of his equipment, having sold or bartered it away. My sentiment is rooted more in memory and a little bit of his art. I’d still own an Alcedo Micron.[note got one last week,seduced by my own story-- worth the wait. Despite its tiny size, it is all machined steel inside, like a 1950s racing machine -- no postmodern technical crap here. It was packed in a grey industrial goo which I had to wash out with rubbing alcohol, and replace with light machine oil. Now it runs more smoothly than all my modern ones]. The last of his tackle I possess is an odd assortment: the aluminum fly box and motheaten flies, some older than me,that will never see the water; a leather and fleece Wallet for streamers, which I use; and most ridiculous here in the high mountain desert of New Mexico; the Penn Squidder, still loaded with braided linen Cuttyhunk line.

A photo of him stands on my desk, a portrait in profile, obviously on a sailboat, the wind ruffling his white hair, sunglasses shading his hair. He is in the place he loved best, off St. Croix, in the islands. I often think of it as the Old Man, or the Old Man of the Sea. He is four years younger than I am now.

The gun in the first photo, with a woodcock in Easton MA, is Betsy's Parker 16. Photo of Betsy with Maggie on West Mesa Alb NM ca 1982.In the 3rd photo I am holding the damn "rich man's gun", my first custom- ordered "bespoke"gun,, an AyA XXV 28 bore, a lot cheaper than his Model 21

Fact is, Joe Bodio was not a sad nice guy. He was a passionate conflicted sometimes brilliant guy who first taught me to love his passions- fishing, hunting, art-- and when he succeeded, seemed to turn against them and me for thirty years. Not a nice guy at all. This is the story of a difficult man's redemption, and it is interesting mainly because of that.

I know, because I am the artist's son. This is the first time the whole story has ever been published.

Illos too!

Predestination...

Striper hipster

At around the age of thirty, an observation by Elizabeth Katherine Huntington that I was “an artist with nice guns” struck me with unexpected force. I realized that I had become a man my father always wanted to be. And that he hated it. I was an artist only in the broadest sense, a sportsman with a madness that has a little to do with ability and a lot to do with obsession, successful only in the smallest of subcultures, but had my very successful father ever wanted to be anything else?

******

See: in the early 1950’s, a very young man in a three-story Dorchester walk-up, a first generation American born to immigrants from the Swiss border fueled by passion and talent, married to a pretty young woman of a different class and ethnic background, with nothing to show but those passions. At that time he really was an artist: a painter a sketcher a sometime sculptor – and a man with a passion for animals, fish, birds, mammals, their shapes and sizes and feathers and movements. In a dingy blue-collar neighborhood, all my early memories are of animals, alive and dead dirt-common and exotic. All before I was five, because of their context; black gas stove with blue and gold flickering flames, basement coal chute, blacker than black, dust on your hands, there stories, white-fenced porches on each level. Its only existence is in a few molecular memories—Google Earth shows the very street vanished below the obliterating white geometry of Ashmont Station.

Against this faded dream: a flash of the most intense blue I have ever seen, edged as for emphasis with black and white. It is the shimmering speculum of a “Black mallard” – Yankee for Black duck – which he takes from the pouch in the back of his coat one morning followed by three more. I am mildly confused because it is NOT black but a rich chocolatey brown. I already know my colors. At four, how would the artists’ son know? My father works as an “engineer”, which I don’t understand because in my mind an engineer drives trains. But not long-ago Dad was a “scholarship student at the Museum School”. And Mum was a commercial artist, drawing models in furs for Kakas of Newbury Street. The relic of which is another fascinating animal, a full-length ocelot coat.

But the ducks…like other beings soon to come, the ruffed grouse, the flounders, the stripers, the brookies, the hornpout, the yellow perch, the mackerel and soon, the tuna and the white-tailed deer, they were all I could focus on as long as they were visibly themselves. And then they became holy relics. I kept those feathers for a decade.

My father let me carry it to the table. That it was dead did not bother me. The only live animals I knew were English sparrows, pigeons high overhead, as remote as angels, and the ragman’s blinkered horses. I had found a dead mouse in the bedside water glass, a dead pigeon in the yard covered by live ants, my cousin’s dead cat, Snoozy smashed in front of my house on Templeton Street. It might be human nature, or something genetic in the artist’s boy, or a little of both, but I found them far more interesting than my little metal plane with the rotating blue propellers, or my toy trucks, maybe an undiagnosed case of Biophilia, not yet invented by Ed Wilson but already hinted at by Aldo Leopold: “…the man who does not like to see, hunt, photograph, or otherwise outwit birds or animals is hardly normal. He is super civilized, and I for one do not know how to deal with him. Babies do not tremble when they are shown a golf ball, but I should not like to own the boy whose head does not lift his hat when he sees his first deer.”

So: dead heavy, limp, wet feathers shimmering like watered silk when I stroked against the grain, deep and thick and soft against it. I could have handled them for hours, but Dad had something else in mind.

He set them gently on the table or rather on the newspapers my mother had provided set one on its back and stripped off a couple of big chunks of feathers against the grain. He smoothed them out in his palm to reveal a single feather, crossbarred with light pencil lines. “I’ll teach you how to tie flies”, he said. “These are the feathers that make wings for flies.” Perhaps he saw the incomprehension in my eyes because he grinned. “Flies – to catch fish. Trout.” He went out, put the feathers down, and came back with a shiny silver box. When he pointed out the wings I could see they were the same as the ones we’d taken from the dead bird. Do artists, or artists’ kids, imprint like birds? Sixty some years later I’m still dazzled by the treasure he revealed in that box. And I still have it, and a few flies I’ll never fish.

The next event in our lives brought us much closer to fish and birds and nature and game. In 1954, we moved to what my mother considered wilderness. These days with Easton a crowded bedroom community located rather less than twenty miles south of downtown Boston, this would seem ludicrous. But in those days, my urban maritime mother wasn’t far off. Easton still had dirt roads, and its population of Yankees, rich and poor, and ethnic Portuguese looked not to Boston but to New Bedford and Taunton to the south, to cranberry bogs and whaling towns. Not a few of the oldsters there had never been to Boston and had no intention of going. To me the raw subdivision hacked into the fringes of a boggy seasonal swamp was a paradise for a novice hunter – gatherer. For our first two years, our basement had six inches of water and three species of calling frogs in it. To me, in today’s vernacular it was a feature, not a bug; not the result of a cynical ploy to fleece the World War II generation, but a habitat.

Dad eventually put in a pump and got rid of the frogs, but I don’t think he was bothered by them. He ramped up his leisure time activity even as I filled my jars with frog spawn, and often took me with him. It was around this time that I caught my first trout in his company, in what was then known as the Blue Hill River. In 1955 it still contained native brook trout, and again the artist’s eye rewards me. My father had been fishing a cast of wet flies, something that he did so often then that a part of my brain still considers it the only way to go. After a while he sat down on a rock and asked me if I would like to catch a trout. He was always a fisherman whose artistic purity fought his dogged north Italian pragmatism but right now neither seemed relevant. He took a coffee can out of his box and hooked a squiggle worm on to, if I remember, one of the flies. “They like these better”. He rolled the line lightly upstream and put the rod in my hands, stripped line for me, and then raised the rod tip, which began to dance. “You’ve got him! Reel him in.” He actually grabbed my little hand and whirled it around the reel as he backed up until it skittered on to the bank. “you’ve got him!”

I did have him. He was probably five inches long, but the red and white in his fins and the mottled vermiculations of his back glow in my memory as the most beautiful fish I have ever seen. That night we ate him fried in butter. Need I say that I still do that?

Today, I’m sure the Blue Hill River exists. Last I checked, it was a trickling culvert under what was then Route 128, now a part of I-95, neither of which were built when I caught my trout. But such tiny natives were always an almost invisible reward for those who shunned more popular quarry. They may be gone from the Blue Hills, but my friend and contemporary Paul Dinolo, a retired teacher, still catches, releases, and occasionally eats my trout’s close relatives in the numerous dark cedar bogs of Plymouth County .

The next fish I remember remains at the opposite end of the scale. I did not see it caught, off Chatham, in my father’s deep-sea saltwater phase, but discovered it beached in the shingle, waiting to be cleaned. For no reason an adult can fathom, my first reaction, and my little bother Mark's, was to take off our shoes and WALK on them.

Maybe it was just a wordless testimony to their size. Although they were all what we would soon learn to call "just little schoolies", weighing no more than 100 pounds, most less than 50.They were the biggest fish we'd ever seen. In retrospect, they were probably the biggest my father had ever seen, which explains why his reaction was to beam at us, rather than to snap at us, "Get off the fish", which would have been more in character.

It was probably the beginning of what was the most idyllic period of our sporting relationship. There is something sweet about teaching a child to fish especially if all the material, from bait to quarry, is near to hand. We had Knapp's pond, now a eutrophicated "wet meadow" but then a gloriously productive pond with three species of game fish broadly defined; no, actually more than that. There were three species of sunfish alone, including big bluegills, an edible spiny catfish which most people today call black bullhead but which we called hornpout, and sinister but elegant chain pickeral. Not to mention a diverse herpetofauna including many snakes and more amphibians which interested my dad as well, though not the rest of the family -- another little bond. My father was always a naturalist.